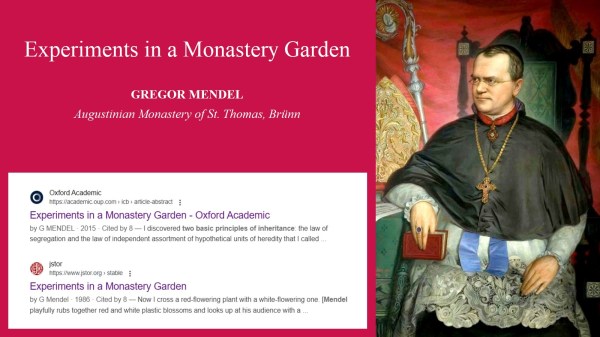

This was a Gregor Mendel’s talk, titled “The Experiment in the Monastery Garden”, in English version, downloaded from Oxford Academic website on September 23, 2022. We respectfully introduce it to the readers.

https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-abstract/26/3/749/264329?redirectedFrom=fulltext

SYNOPSIS. After a brief account of my early education, study at the University of Wien, and preliminary experiments on hybridization conducted at the Augustinian Monastery in Br Brünn, Austria, I state the reasons for selecting certain features of the edible pea, Pisum sativum, for extensive investigation of their inheritance. After eight years I reported my results to the Brünn Society for the Study of Natural Science, and they were published in the following year (1866) in the Proceedings of the Society. I discovered two basic principles of inheritance: the law of segregation and the law of independent assortment of hypothetical units of heredity that I called Elemente. I conclude with some remarks on the possible relation of my work to the evolution of organic form and on my disappointment that my studies do not seem to be known or understood, and that because of my administrative duties at the monastery, now being the Abbot, I have no time for further investigations

Danke schon, Herr Professor Moore. Grüss Gott, meine Damen und Herren. My lecture this evening, as announced by your Vorsitzer, is on the inheritance of hybrids in the common edible pea, genus Pisum. My interest in heredity began already as a boy on my father’s farm in Heinzendorf in Moravia, a province of Austria. My father had horses and cows, chickens and bees, peas and beans, and flowers—always flowers. Being a curious and uninhibited boy I observed breeding in animals and seed formation in plants. I found breeding of animals more interesting. I often wondered why the offspring resembled their parents but were usually not exactly like their parents. We had a good teacher in the Heinzendorf school that had opened its doors only thirty years earlier. Previously the boys and girls of Heinzendorf never learned to read or write. Their parents were too poor to send them away to school. From my teacher I learned much, including growing fruits and keeping bees.

When I completed the school my teacher told my parents that they should send me to the high school in a town many kilo-meters away. With great sacrifice to them I went, but it was hard to keep body and soul together. Part of the time I was on half-rations. Eventually, it appeared that I must discontinue my studies and begin to earn my own livelihood. But one of my high school teachers recommended me to the Augustinian Monastery of St. Thomas in Brünn. I was accepted and became a novice. Later I took my vows in accordance with the rule of St. Augustine. After a few years my order sent me to the University of Wien with hopes that I would pass the examinations and become an accredited teacher. Well, I did not pass my examinations, and so I returned to Brünn and became an unaccredited teacher—a good one, I am happy to say.

My interest in plants and animals, begun on my father’s farm, as I have explained, continued during my school years and at the University of Wien, and became my primary preoccupation at the monastery when I was not engaged in teaching and religious duties. I always kept bees and mice. But I did not like snakes. Yet my boys brought them to me because they knew that I did not like snakes. My animal breeding in the monastery, however, was regarded as immoral by my superiors because it appeared that I was playing with sex. I had to be particularly careful not to incur further disfavor of the bishop, a conservative cleric and a very corpulent man. You see, I had made the mistake of remarking to some friends that the bishop carried more fat than understanding. Someone reported me, and after that the bishop and I were not good friends. Incidentally, little did I know at that time that I too would acquire stout proportions. [Mendel pats his stomach.] So I turned from animal breeding to plant breeding. You see, the bishop did not understand that plants also have sex. Gelt?

I had long grown ornamentals for their lovely flowers, and I had learned to cross- pollinate them to obtain interesting hybrids. But these plants were not suitable for the study of inheritance. After trying several kinds of plants I found that the common garden pea was most satisfactory, for several reasons. First, seeds of several varieties could be obtained from seedmen in the town. Second, the plant grew well in the little plot assigned to me in the monastery garden. Third, its flower is ideally constructed for experiments in hybridization. Normally the plant reproduces by self-pollination. But this can be prevented by removing the stamens, the male organs, before the pollen is ripe. The flower is like this. [Mendel uses his hands to illustrate.] Simply spread apart the petals to reveal the sex organs inside. Pull out the stamens with a pair of tweezers, leaving the pistil, the female organ. Cross-fertilization can then be accomplished by dusting pollen from a ripe flower on the pistil by means of a small brush. The petals enclose the pistil so well that fine airborne pollen cannot enter. Thus the chances of contamination are slight, but I never relied on it. There is the pesky pea weevil that can enter the bedroom chamber. So I always tied paper bags over the flowers in my experiments. And four, there are other advantages to peas. They are nutritious. 1 usually carry a pocketful of them to satisfy my yearning. [Mendel produces handful of peas from his clerical gown and pops some into his mouth.] And when my boys pay no attention to my lectures or they fall asleep, I simply ask the Almighty to send down a shower of peas. [Mendel peppers his audience with peas.] That wakes them up! Gelt?

After a few years of preliminary studies to test the purity of my seeds and to select features for study I began my experiments in earnest in 1856 and finished them eight years later, after studying over 10,000 pea plants. I presented my results in 1865 to the Brünn Society for the Study of Natural Science, and they appeared in the Proceedings of our society in the following year.

I found that some features had clear contrasting traits such as tall and short vine or either red or white colored flowers. In all I selected for study seven features with clear and distinct traits. The seven that I chose were color of seed, shape of seed, color of pod, form of pod, color of flowers, position of flowers on the stem, and length of stem. For each of these features one of the traits was dominating and the other was recessive. For example, red flower was dominating over white flower; and tall vine was dominating and short vine recessive. I illustrate what I mean by dominating and recessive.

I have here some red and white sweet pea blossoms. Let us assume that they are flowers of the garden peas. Now I cross a red-flowering plant with a white-flowering one. [Mendel playfully rubs together red and white plastic blossoms and looks up at his audience with a grin.] It makes no difference in the results whether I dust the pistil of the red flower with pollen from a white one, or vice versa. All of the next generation plants have red flowers, one hundred percent—not a single white flower. Now, is the white trait lost? No! When I cross two of the first generation plants, lo and behold white flowers will appear in all their purity. The whiteness was only suppressed by the redness, and that is why I call white recessive and red dominating.

Of course, there were red-flowered plants in the second generation offspring. When I counted them there were about three of the reds for every one of the whites. The ratio is about 3 to 1. Now I say “about”—it was never exactly 3 to 1. As examples, I quote from my paper. In one experiment I had 929 plants: 705 had red flowers, 224 white ones. The calculated ratio was 3.15 to 1. In another instance, the ratio was 2.95 to 1.1 think that if I had produced more plants my ratios would probably be closer to the theoretical 3 to 1.

I now proceed to analyze the second-generation plants. We discover, not unexpectedly, that the white plants when crossed with white give white flowers. Actually, it is easier to allow a white-flowered pea to self-pollinate. Thus pollen from a white flower fertilize ovules in a white flower. Obviously, the whites are a pure line. Consider now the red-flowered plants: one third of them turn out to be pure red-breeding. When crossed with each other, or when you permit self-pollination, they produce only red-flowered plants, just like grandfather. The other two-thirds of the second generation reds are like father and mother—hybrid red—because upon interbreeding they give a 3 to 1 ratio of red to white. So you see we have actually three kinds: pure red, hybrid red, and white. And the ratio between the kinds is 1:2:1. Gelt?

[Mendel suddenly notices a stem with pink flowers. He picks it up.] Ach du Lieber! Was ist das? Pink flowers? They should be only red or white! [He tosses the pink flowers away.] I think that some student has played a trick on Pater Mendel. Also I began to think of discrete hereditary units. I called them Elemente. They pass from generation to generation through the pollen grains and the ovules. Now there must be an Element for whiteness, a recessive, and a dominating Element for redness. When they are together in a hybrid, the flowers are red. But the Element for whiteness is there, all the time. It will not be lost or contaminated. I then devised a simple system for recording the Elemente, to save much writing. I said let the letter A represent an Element for flower color with capital A standing for the dominating Element and little a for the recessive Element. Now hybrid red, because it has both Elemente, should be expressed by Aa. When the hybrids produce pollen and ovules the Elemente separate from one another so that in the stamens two kinds of pollen grains are formed, half of them possessing large A and half of them little a. Likewise in the pistil two types of ovules will develop: those with A and those with a. Gelt? This separation of the Elemente I called the law of segregation.

You must understand that I was not the first person to study inheritance. Men and women have been breeding plants and animals since ancient times and some scientists have tried to discover the principles of heredity. But why did I succeed whereas others failed? One reason is just this: I selected a few features with well-defined, contrasting traits to study in an organism that was suitable for experimentation. My predecessors, however, tried to study the whole organism at once. But inheritance is complex. One must simplify the investigation, study one pair of contrasting traits at a time. And then you may study two traits together, as we shall do presently. Only in that way can one discover the secrets of nature. Then second, I used quantitative methods. I counted peas, and peas, and peas! I kept very careful records, and I calculated ratios. During the long winter months I worked with my seeds, counting them, placing them in properly labeled envelopes, posting my accounts, doing the calculations, and planning the experiments for the next spring. Hard, tedious labor, but that was how I succeeded. I shall not say that my predecessors were lazy. I was willing to work with zeal, patience and with the stubbornness of my peasant ancestry.

Also. Having studied all seven features with clear contrasting traits and learning that each one obeys the law of segregation, I proceeded to study two or three features simultaneously. Let me illustrate. Suppose we cross a pure-breeding red-flowered, tall pea plant with a white-flowered, short one. Now we must choose a letter to stand for length of vine, the second feature. Choose letter B. Again the large B represents the dominating Element for tall; the little b stands for the recessive one for short. So I write AABB X aabb. All of the first-generation offspring will be hybrid red and hybrid tall or AaBb. Gelt? This follows from the law of segregation.

Now let us cross two such hybrids or simply allow self pollination. I then discovered my second principle, the law of independent assortment. That means the Elemente for one feature (flower color) segregate independently of the Elemente for the other feature (length of vine). Thus there are four types of pollen grains: AS, Ab, aB, and ab; and there are the same four types of ovules. Next, we analyze the second-gen-eration offspring. [Mendel uses a Punnett square—an anachronism—to explain the four phenotypes and nine genotypes and their ratios. And with a table he demonstrates the arithmetic progression in numbers of gametes (pollen and ovules), phenotypes (traits), and genotypes (kinds), and the combinations of gametes in crosses of hybrids.]

Also! What are these discrete Elemente about which I have been speaking? I wish I knew. My microscope does not greatly magnify. I can see the tiny pollen grains but not the Elemente inside them. I hope that someday a powerful microscope will be invented so that we can see the elements of inheritance. And perhaps someday clever chemists will be able to tell US their chemical composition. Much more work needs to be done on inheritance.

Recently I had a conversation with some visitors in the monastery garden. One member, a botanist, asked: “What is the relationship, if any, between your work and the origin of a new species?”

“I am convinced,” I replied, “that my studies on hybrids are of significance for the evolutionary history of organic form.”

They pressed me further. “Was I acquainted with the writings of Charles Darwin?” “Yes, indeed,” I said. “I have read almost everything that he has written on the subject of evolution. Our monastery library contains many of Darwin’s books and also Zoonomia by his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin.”

“I have long thought that there was something lacking in Darwin’s theory of natural selection. And I have also questioned the views of Lamarck. I once made an effort to test the influence of environment on plants. I transplanted certain plants from their natural habitat to the monastery garden. Although cultivated side by side with the form typical of the garden, no change occurred in the trans-planted form as a result of the change in environment, even after several years. Nature does not modify species in that way, so some other forces must be at work.” My visitors then asked me about new experiments that I was conducting. I sadly looked about the garden. Not one of my plants could be seen. All were gone. I have become so burdened with the administration of the monastery that I no longer have time for experiments. Much of my time and energy is required to fight the state government for money to educate my boys. The government does not seem to realize the importance of education. Maybe this is your experience also. And I have become discouraged. Few appear to know about my work—not even Charles Darwin. But I take comfort in the thought that science is always moving forward, although slowly at times. Sooner or later—sooner or later—my work will be repeated, and I shall be either right or wrong. In the meantime I must have patience. I think that my day will come. That is what I tell my boys. I say to them: “Work hard, work with joy, and work with patience. And I often commend to them that verse in the Book of Ecclesiastes: “The patient in spirit is better than the proud in spirit. Therefore, be not hasty, and be not angry: for haste and anger rest only in the bosoms of fools.” May God bless you.

Note (1)

1) From the Symposium on Science as a Way of Knowing—Genetics presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Zoologists, 27-30 December 1985, at Baltimore, Maryland;

2) From Great Scientists speak Again by Richard M. Eakin, copyright © 1975 The Regents of the University of California, by permission of the University of California Press